Practice and Representations

I use "x-axis" and "y-axis" in a musical context

I very much disliked practicing in high school. I mean, who doesn’t dislike practicing?

So, in high school, I wanted to do everything in my power to reduce the amount of time I had to practice. Which, I assumed, meant that I had to increase the quality of the practice.

Thus, I read a book.

When I was preparing my classical auditions for college music programs, I read Peak by Anders Ericsson, which explains the theory of deliberate practice. One of my favorite topics in Peak is mental representations, or how experts think about their craft and evaluate their performance. Ericsson summarizes his theory by writing:

“… one could define a mental representation as a conceptual structure designed to sidestep the usual restrictions that short-term memory places on mental processing.”

Everyone builds mental representations, even if we don’t think about it. For instance, consider driving a car: we think about our own speed, the speeds of others, the position of the steering wheel, the road conditions, the position of the accelerator, the force applied to the pedals… there’s no way anybody could drive without, in some way, creating a mental representation of the driving experience.

There are more complex examples as well, but my favorite is chess. Top-rated chess players don’t keep track of every single piece on the board. Instead, they “chunk” the board into sections of functional groups, and describe the state of the game using abstract notions like “lines of force.” They hold a mental representation that allows them to quickly process large and complex sets of information.

Everybody uses mental representations, but experts and high-performers are distinguished by the quality and quantity of their mental representations. Thus, the goal of deliberate practice is to refine and improve mental representations.

Turn Your Eyes Upon Jesus / Holy Forever (watch it here)

Now, let’s say someone wanted to improve their MDing. How could they practice in a way that improves their mental representation of MDing?

Everybody’s different, but for me, I used to practice MDing by drawing the shape of a song.

Now, I can already hear you. “The shape of a song? How does a song have a shape?”

For me, songs didn’t used to have a shape. I would practice by memorizing each portion of each song, treating each song as distinct. It was not a good mental representation. Ericsson would critique my method, pointing out that considering each song as completely unique requires a lot of computational power and memory.

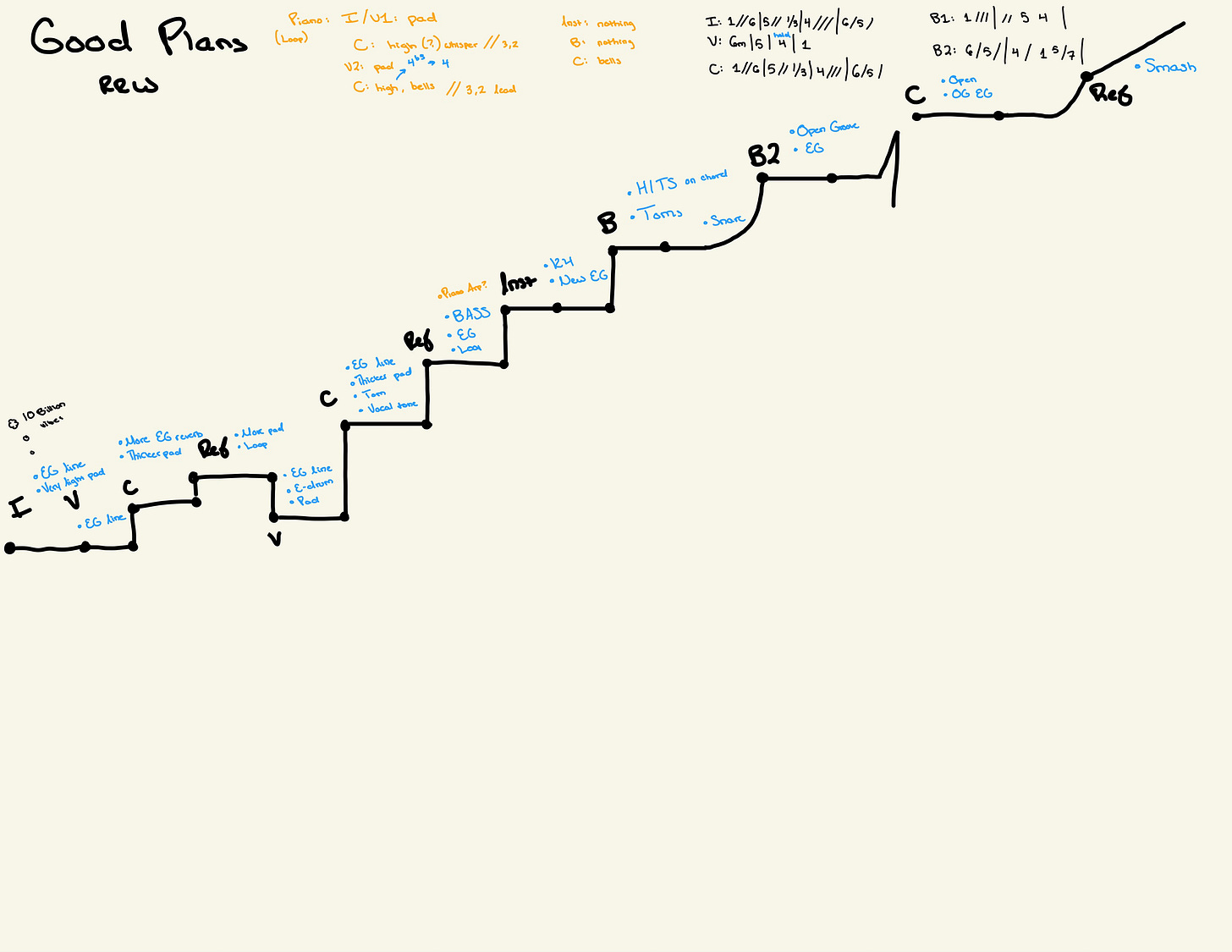

So, I practiced abstracting the details of the song. I would create plots like this, with time on the x-axis and “energy” on the y-axis.

After practicing like this for a month, I stopped doing this for every song on a weekend. Now, I’m at a point where I can digest the song by listening to it, generate a notion of the song’s shape, and use that shape as a structure to store in my long-term memory.

However, I’ve recently wrestled with how this abstraction - this very pragmatic approach to learning worship music - can seem to diminish the reverence and holiness of worship. I can trivialize a worship song, saying, “Oh, it’s like every other worship song: it starts low, builds up to the second chorus, drops for the bridge, builds up again during the bridges, hits two big choruses, and then ends.” I can go on auto-pilot during worship and forget to engage.

But, it would also be absurd to suggest that I shouldn’t practice, that I shouldn’t pursue excellence in my worship. Surely, my worship would be more dishonoring if I was completely overwhelmed by the complexities of the song and only focused on the music.

What, then, is the function of mental representations in worship?

For me, these mental representations occupy my restless mind. I pray that it does not diminish the holiness of my worship. Instead, I hope that it allows me to move out of the way of myself, to approach something more complex with my spirit instead of my mind.

Consider this: if there’s mental representations for my mind, are there a “spiritual representations” for my spirit? The holiness, the splendor, the goodness of God is incomprehensible to a fallen Creation. That’s why we use human structures to describe God and our relationship to Him despite their inability to fully capture His complexity. He’s our Lion, even though He’s also our Lamb. He’s the groom and the Church is His bride, even though He’s not actually married. He’s our Father, even though we were created and not begotten.

In my experience, which is surely more poorly informed than the experiences of others, these representations are more than just a mental representation. I emotionally relate to God differently when I consider Him as a Father, and I do so in a way that differs from the mere mental exercise of thinking about Him as a parent. There’s a different sort of representation.

And, if we can have a “spiritual representation” of God, that insinuates that we can also engage in “spiritual practice.” At this point in my faith journey, I want to practice this intentionally. If I can just get my restless mind out of the way, if I can distract it with a mental representation, then I can focus on my spiritual practice.

So, when I worship, my mind thinks of the shape of the song, and I engage in a different sort of practice. I smile when I think of how much more complex His nature truly is, and how overjoyed I am to even experience a sliver of it. Every weekend, I get to refine my spiritual representation of my Savior.

Now, I guess you could say that I very much enjoy practicing. It’s just a different sort of practicing than I used to do. And I love to do it.

Here we go,

Isaac